Voices from the Future | Larry Baimbridge

Swallowed by Water

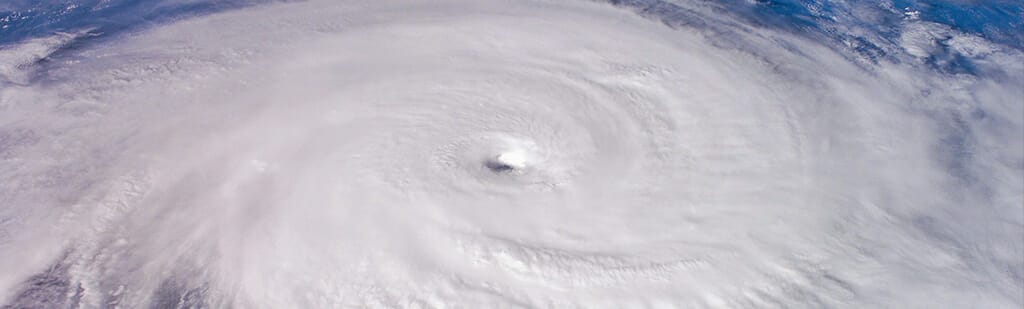

The Event: In 2017, Hurricane Harvey hit Houston, Texas, with sustained 130 mph winds, torrential rains and flooding. Thirty percent of Harris County, which has a population of 2.3 million people, was flooded. Eighty-two people lost their lives.

Police captain Larry Baimbridge and his wife, police officer Wendy Baimbridge, were at work when Hurricane Harvey hit on August 27. “I knew our house was flooding and our two dogs were home,” he says. “Luckily, our neighbors rescued the dogs that had stayed on the bed, when the water started to come inside. We were on a 24-hour shift and couldn’t leave.”

At that point, as captain for the police dive team, Baimbridge had mobilized eight boats, four highwater vehicles and a crew of 25 men for a rescue mission in the Houston area. In fact, for the next four days, Baimbridge and his wife had little rest as the hurricane-induced storm brought torrential rains and made three landfalls in Houston and its coastal areas.

“Some houses that were closest to the city waterways were swallowed by at least 10 feet of water when we arrived,” he says. “For us, Harvey was hard to follow. First, it hit the southwest and then the northeast part of the city. Later, the levies started to burst, and flooding happened in new areas, even though the rain had already stopped.”

When all was said and done, Baimbridge and his men saved 3,000 residents from the flooded houses and streets. They also looked after local civilians, who helped the rescuers during the operation.

“Once a street that you know so well has turned into a raging river, it can pull you under when you least expect it,” he says. “The other challenge was swift waters. Luckily, we did not bump into houses or mailboxes or fire hydrants and cars that were under water and cannot be seen from above. We also came across people who refused to leave. A lady in her 90s who had Alzheimer’s was fighting us because she didn’t understand what was going on. We got an older man out after I told him that he was evicted. It wasn’t true, but that was the only way to get him out.”

Baimbridge witnessed community members chipping in, too, often in unexpected ways.

“One time, our boat was full. At the end of a long road that had turned into a river, there was a house that hadn’t flooded,” he says. “The owners of the house invited us to bring evacuees inside and offered shelter and pots of chicken soup and warm cookies to us and everybody we brought in for the next four days.”

Although Houstonians aren’t new to hurricanes and flooding – the last big one that Baimbridge, 49, experienced was Hurricane Alison in 2001 – Harvey and its force and floodwaters took him by surprise. He has lived in the area all his life and is used to living on low land. But even Baimbridge wasn’t prepared for Harvey.

“Alison was pretty bad, and it stalled over Houston for 16 days and everybody — me included — thought this is the worst it can get,” he says. “With Harvey, the excessive flooding was the biggest problem. There was no place where the water could go, since the area has grown so much. When I was young, we had about a million people, now the number has almost doubled. With that growth had come too many houses and streets, and mitigation efforts that haven’t been able to keep up with the new development.”

It might be in the nature of his profession, but Baimbridge doesn’t dwell on the past or reflect too deeply on Houston’s environmental damages. But, they did prepare for potential future flooding when, this year, they moved into the city from the suburbs, even though they’d spent five months repairing the home that flooded during Harvey with the help of volunteers.

“Again, the help that we got from the community ripping off the sheet rock and rotten floors was just great. I am very grateful,” he says. ”We moved because of our son’s school. But elevation was first in our minds when we looked for a place. We made sure that the house is two feet up. Houston is very flat, and two feet up is already a lot and gives us protection when the next floods happen – but, hopefully not in a heartbeat.”

— Kirsi-M. Hayrinen-Beschloss